19 Dec 2023

They are unique and their value is incalculable. Among them are the “Blessed Morgan”, the “Hours of Joan of Navarra”, both made in Spain, and the volume that contains the “Carmina Burana”.

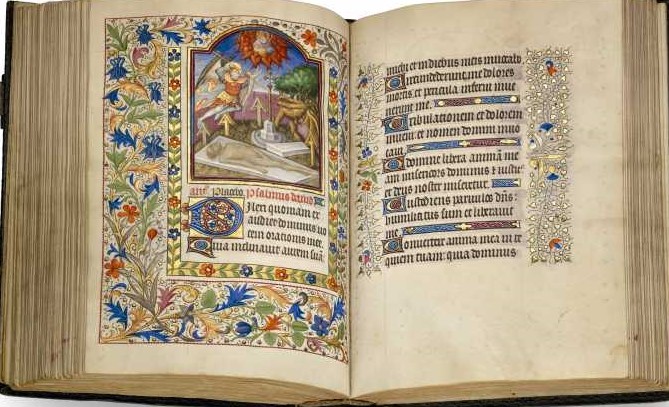

Medieval manuscripts have exerted a powerful attraction on the popular imagination. They always remained shrouded in a haze of mystery as if they were transmitters of remote secrets or forgotten knowledge. An idea that has inspired many, suggested a multitude of stories and inspired novels of varying success and quality. But his heritage is richer and more abundant. The importance of these volumes lies not only in the texts they transmit but in the history they carry with them. Christopher Hamel, one of the world's leading experts in Ello, librarian emeritus of the Parker Library of the Corpus Christi Colledge in Cambridge, examines twelve of the most important codices in the volume "Great Medieval Manuscripts" (Attic of Books), illustrated pages with 200 images that represent a tour of the libraries most relevant in the West.

A journey that goes from New York to Saint Petersburg, and that puts the reader in contact with kings, thieves, scribes, copyists, tabernacle monks, vagabonds, multimillionaires, collectors and composers associated with the Third Reich. But this selection of codices, which explain their origins and vicissitudes, is also a review of the sensitivities, concerns, beliefs and fears of their time. An idea evident in the "Blessed Morgan", from the mid-10th century, which is preserved in the Big Apple. A piece of extraordinary importance that was written in the monastery of San Salvador de Tábara, Zamora. He belongs to the so-called "Beatos de Liébana" (which Eco popularized in "The Name of the Rose", where it is cited). Each copy included the commentary on the "Apocalypse" by a Spanish monk from the 8th century: Beato de Liébana. It was a kind of "best seller" of the Middle Ages. Its disclosure would be extraordinary starting in the 10th century, with the approach of the year 1000, a date with the same aura of misfortune that surrounded the arrival of 2000. Then it was more serious because they considered it to be the end of the world.

Believers and lifers

Hamel describes the fear of that tremendously believing society and explains how these pages were a call to contrition and the awakening of faith. But for him it is also relevant for other reasons: it is the oldest copy of this text that is in conversation with the original cycle of illustrations. And, furthermore, it has an unusual feature: it contains the signature of the master miniaturist, Maius, who in these pages admits that his intention is to create fear among believers with his images and affirms that he was the man who designed these drawings (which are so popular). became popular later). It is, in all probability, the first claim to artistic authorship that exists in Europe. The «Blessed Morgan» was rediscovered by Guglielmo Libri. A liveist and man of many faces. He turned out to be an advance of paleography, a scholar and a sensitive talent towards the writings of the past; but also someone unscrupulous who stole documents from other collections, remade the books, manipulated them, falsified inscriptions and dismembered volumes for his benefit.

This work is not the only one of Spanish origin that Hamel recovers. It also affects the future of a work of incalculable value: The "Hours of Juana de Navarra", from the mid-14th century. A highly appreciated liturgical work that was part of the personal art collection of Nazi leader Hermann Göring. At the end of World War II, American and French troops They entered the Berghof, Hitler's private residence. In its vicinity, and after a shootout, they stopped a train. The allies discovered an unexpected cache inside: the wagons were loaded with paintings, sculptures and jewelry. An officer tripped over an oblong box containing a manuscript. Since soldiers considered it a war custom to take home some of the spoils of war, he did not hesitate and took it with him. Some time later he donated it to the abbey of Boquen, in Brittany, and the abbot, when trying to pay for the works to reform the monastery's roof, put it up for sale. In this way it came to light in France. The "Hours of Joan of Navarre" (which contains an exceptional detail: portraits of the queen herself, its owner) belonged to the exquisite library of old books by Edmond de Rothschild. But in April 1940 it was looted by the Nazis and the most valuable copies were sent to Göring. The surprise came later, when some documents recognized that the German government had compensated the heirs. The debate over its membership and whether it should travel to Berlin or stay in the French National Library strained diplomatic relations between the two countries. But the dispute was settled when it was declared an unexportable cultural asset in France. Since then it has been kept there.

Hamel also collects in its pages the history of the "Codex Amiatinus", from 700, which preserves the oldest version of the "Vulgate", the Latin translation of the Bible made by Saint Jerome in the 4th century, but also of the "Aratea of Leiden", from the beginning of the 9th century, which must be related to the Carolingian Renaissance of the late 8th and early 9th centuries, and which represents one of the first attempts to recover culture, in this case, the science of Greece and Rome. There is no shortage of the “Book of Kells”, from the end of the VIII century, which is exhibited in Dublin and is the attraction of the Trinity College library. It is considered an icon in the country, as demonstrated by the thousands of reproductions of its pages found in Ireland. His particularity lies in the way he articulates Christian iconography with Celtic tradition. By reconciling the faith of the cross with paganism, a spectacular artistic imaginary emerged.

A Nazi exaltation?

But among the manuscripts he mentions, some strange pages draw attention, what seems at first glance to be a prayer book, with its psalms and liturgy, but when examined carefully it provokes surprise and then astonishment. It appeared in the 19th century in the monastery of Benediktbeuern, Upper Bavaria, when, due to Napoleonic laws, it closed its doors in 1803. Baron Johann Christoph von Aretin was captivated by the magnetism of its images and their rarity. When he was appointed director of the Munich State Library, where it still remains today, he deposited it in his archives. From then on it will be part of his funds. His fame spread quickly and, in fact, he was even consulted by one of the Grimms, Jacob, to whom one of the first editions is due. But what did it contain? Just what a historian least imagined finding in a medieval work. Any scholar expects a real chronicle, the description of a battle, a book of a religious, philosophical or, in the least case, scientific nature. But what was there was “singing lasciviousness.” In this fortuitous way, the most humorous voice of the people appeared in a work. There were the "Carmina Burana", the songs that vagabond clerics and students sang in taverns. They were poems in Latin and other languages that exalted carnal love, women, spring, drink, money, gambling, and who had Fortune and her wheel as their goddess, which, as their verses say, today makes a king govern and the next day precipitates him and leaves him ruined in poverty.

An unknown Middle Ages came to light. These 254 poems, which use vulgar and irreverent language, together with the dramatic texts they contain (mainly from the 11th and 12th centuries), attracted a young composer in the 1930s: Carl Orff. He bought a reproduction of the poems in 1904 and immediately became fascinated by the first one, the one that begins "Oh Fortuna." Helped by an archivist friend, he studied the text, investigated the meaning of "Burana" and signed a controversial score that has always enjoyed public support. "Carmina Burana" premiered on June 8, 1937 in Frankfurt. The Nazis had already been in power since 1933 and the composer's political position was never clear (nor did he help clear it up). Joseph Goebbels, after attending a performance, wrote in his diaries: "He displays exquisite beauty, and, if we could convince him to change the lyrics, his music would certainly be promising." "I will send for him to come and meet him as soon as possible." Doubts about whether this score was a piece of Nazi propaganda or not have always hung in the air. North American critics have always complained about its excessive pace.

AN OLD PORTRAIT

Among the twelve codices that Christopher de Hamel collects in his book, two others stand out for their impact on culture. The first is known by the name "Hugo Pictor" and is dated to the end of the 11th century. Its pages keep an important secret. The author's name appears, but next to his portrait, which can be seen at the beginning, which is unusual. In this "selfie" he is drawn as a monk sitting in front of his lectern, absorbed in his tasks as a copyist. It is, without a doubt, the first portrait in the history of English art. Another manuscript, less known, but also of vital importance, is "Chaucer of Hengwrt", from approximately the year 1400. The particularity of this work is that it is the main source used by current versions of "The Canterbury Tales." , by Chaucer, who wrote between 1387 and 1400 and which for England is one of the most important books of the Middle Ages. There is still a debate around him about who the scribe was. There are specialists who maintain that his authorship has a name: Adam Pinkhurst, the Adam that Chaucer cites in his book.